Fuzzing embedded systems - Part 2, Writing a fuzzer with LibAFL

Intro

In the previous post1 we explored how I chose an embedded device to attack, how to extract its firmware and how to choose a target component to fuzz.

We explored why I chose to research CGI binaries and what they are and how they interact with Linux briefly.

Today we will delve into automated vulnerability research through fuzzing. How to write a fuzzer and how to triage vulnerabilities.

The vulnerability described affects the firmware DSL-3788_fw_revA1_1.01R1B036_EU_EN , it has been fixed and MITRE assigned the following id to track it CVE-2024-57440.

Fuzzing

Fuzz testing (better known as fuzzing) is a dynamic application security testing technique where input is generated (or mutated), is fed to the program and finally feedback is observed for interesting behaviors. Information about the running program is usually collected through instrumentation.

This definition is purposefully vague to comprehend a variety of different targets and techniques, but exposes the concepts which I find to be fundamental for fuzzing.

During the years fuzzers and all the tooling around them was built to trigger crashes from programs written using languages which manage memory manually (e.g., C). This overfitted fuzzers to find memory corruption vulnerabilities, given common feedback loops like edge coverage.

This limitations are being worked on with new techniques like differential fuzzing and different feedback loops like the violation of previously decided invariants2.

So, why use fuzzing? To find vulnerabilities faster (or try to) and with less effort than manual vulnerability research.

LibAFL

Fuzzers are mostly built to do the same stuff, with very little differences or approaches. It can be useful then to have a library that collects the most important parts of a fuzzer while still allowing for customization for different targets and use cases. LibAFL is just that, a library supporting a variety of different techniques and platforms and with great performance as a bonus (thanks Rust!).

LibAFL and MIPS

Ok, so it’s time to build our fuzzer and get free 0days right? LibAFL supports different platforms and architectures. We checked and MIPS is supported, right? Right?

Yeah, LibAFL did not support MIPS when I started this project, and I didn’t bother to check before buying the router. This meant I either could change target or delve into MIPS and Qemu internals to add support…

So, after a few days (and some pain) I managed to add support to LibAFL and the patched Qemu3 it uses. Support for MIPS (with my contribution) was added in the 0.9.0 release4.

I sadly was not able to make the most important feature work, QASAN. This feature allows for ASAN to be used on compiled binaries that would otherwise not support it. We will talk later on why ASAN and sanitizers in general are fundamental when fuzzing for memory corruption vulnerabilities.

Writing the fuzzer

Now that LibAFL supports our target, we have to choose the different approaches which the fuzzer will use to achieve our goal.

The code for the fuzzer is on the Github repository5.

Binary-only fuzzing challenges

Since we don’t have access to the source code of the CGIs we must use a binary-only approach.

With source code we would usually compile the instrumentation used to test the fuzzer statically. Without this we will rely only on analysis we can perform using the binary, which will lose some precision as well as performance (which is a priority when fuzz-testing). Between all the performance decreases we won’t be able to use sanitizers.

Sanitizers are compiler instrumentation modules which are used to detect different errors at run-time. The most popular is AddressSanitizer (ASAN) which can be used to detect most memory corruption errors.

Not being able to use such a tool leaves the fuzzer blind to a lot of vulnerabilities which do not cause an immediate crash of the executable. For this reason LibAFL implements QASAN6, which allows the detection of memory errors in a guest Qemu emulator with a binary-only approach bypassing the need for compile-time instrumentation. As said before, I couldn’t get this part to work for MIPS, which means we will be left with traditional crashes caused by signals like segfault.

Another approach used by a majority of fuzzers is snapshot fuzzing. This is an optimization technique which saves a snapshot of the state of the program (e.g., registers, stack, etc) before the target code and restores it after either a corruption happens or the end of the target function to fuzz is reached.

flowchart TD

a[Program starts] --> b[State is saved]

b[State is saved] --> c[Fuzz target]

c[Fuzz target] --> d[Crash?]

d --> f[Save crash file]

d --> b[State is saved]

It only executes the portion of code between the snapshot and the end of the fuzz target, saving CPU cycles which would otherwise be dedicated to inizialization and destruction code (e.g., to load libraries).

Feedback and objectives

Feedback guides the fuzzer towards interesting code paths. The most common (and easy to implement) feedback is coverage, more specifically edge-coverage. This feedback instructs the fuzzer to save an input as interesting if it leads to the execution of a new portion of the executable, leading the fuzzer to autonomously discover the program.

An objective is an input which causes a state from the program which is desired. In our case we are only interested in inputs which cause a crash, which are sometimes a symptom of a memory corruption vulnerability.

Input

We also have to choose what’s the best approach to create inputs for our target. This can be either:

- Mutational

- Generative

Mutational approaches heavily rely on feedback to mutate a set of initial data (called seed), towards interesting code paths and crashes. This is particularly effective for loosely structured input, or to test the structure of the input itself. It also does not require any knowledge on the target besides creating the set of inital inputs (valid or not). This can be as simple as flipping bits of a valid input, to see if it leads to new coverage.

Generative approaches are useful for highly-structured input, for which most of the mutations would lead to rejected inputs (i.e., getting less coverage). It requires precise knowledge on the structure of the input, meaning some reverse-engineering must be performed.

As the input I will generate will be structured, the first approach would lead to a lot of the inputs being rejected because they’re not valid, while the second approach wouldn’t take advantage of any feedback and simply generate inputs which fit the grammar.

For this reasons I chose to use Nautilus7 which it’s supported by LibAFL, and uses an hybrid approach taking advantage of both coverage as feedback and a grammar which it’s easy to implement.

Harness

To create the harness, we need to know exactly how the input is consumed by the program (e.g., console arguments, standard input, sockets) and, if everything fails, how the input is represented in memory to inject it directly. In my case part of the input is in environment variables which are easy to set, but since they are read right at the start of the program a snapshot could easily break them.

For this reason I decided to inject the input directly in memory.

Part of the input is a linked list in the stack (this is how environment variables are stored) while part of it is taken from the file descriptor 0 (standard input).

For the envinroment variable portion, I decided against storing the testacase on the stack since it might override necessary program data. I stored only the array of addresses on the stack, and then mapped a different portion of memory to store all the test case data.

Also, since snapshot fuzzing is used, we have to understand which portion of code we want to fuzz, and set the instrumentation to stop and resume from the correct addresses.

Grammar

For the grammar I took heavy inspiration from TrackmaniaFuzzer8, which also uses Nautilus, and chose a very simple approach. Context-free grammars can be represented (and are usually processed) using syntax trees. I created the grammar using two main sub-trees. One for the input sent through the body of the request received by the CGI (which is sent using stdin), and the other for the rest of the request (sent using environment variables).

This makes it possible to unparse the tree mutated by Nautilus starting from different rules, thus being able to inject using different techniques.

One subtree is dedicated to all the inputs which have to be sent trough environment variables. The other is for the body of the request, which has to be sent through standard input.

flowchart TD

id1((Root)) --> id2((Environment variables))

id1((Root)) --> id3((POST body))

For both subtrees I chose a very simple approach, which can be greatly improved. First, I created some simple basic types to use in the grammar, as well as “naughty” data which contains stuff to facilitate crashing.

For the environment variables I reverse engineered the executable to searching for the uses for the getenv libc function (and eventual wrappers) to only implement those which are used by the executable.

While for the body of the request I simply created pairs of fields and url encoded strings.

I mined the executable for fields and parameters, which were used in the grammar. This is not the best way to but it’s really cheap (in terms of time spent) and fast (and, as I found out later, it works).

QEMU Modules

Modules (called helpers, in LibAFL 0.8.2) are ways to interact with the Qemu emulator using LibAFL via hooks. These hooks are useful to communicate to the emulator how to react to different events. The modules I used for my fuzzer are two:

- QemuGPResetHelper

- QemuFakeStdinHelper

The first module is used to implement snapshot fuzzing, it saves the state at the start of the execution, and re-stores it every time.

Specifically it restores the registers and the current working directory (because the webproc executable changes it during execution). It does not restore the memory connected to the environment variables because, since it is a linked list of null-terminated strings, everything after the last null-byte of the last string will be ignored.

This means I can leave pieces of old inputs in memory, because they will be ignored, saving precious CPU cycles which would otherwise be used to zero out that region of memory.

The second module is used to hook a variety of syscalls, and specifically hook the read syscall to force the executable into using our testcase in case the standard input is read.

For these hooks, as well as as the general structure of the code, I took inspiration from Epi052 fuzzing101’s soulutions 9.

Triaging

After testing the webproc binary we got some crashes, now what?

Now we have to triage the bugs. Nautilus stores the result of crashes on disk using the representation of derivation trees. This means that to reproduce the crash, we need to first “concretize” the output.

Since all of the grammar functions are implemented using Rust, it was to add a flag in the fuzzer which, instead of running the fuzzer, creates a concretized version of the crashes. (a new executable would’ve been better, but I was lazy)

After concretizing the crashes I then created a small Python script (called repro.py in the repository) to set up an enviroment using the concretized results and then run the executable using qemu-mips to debug it using gdb-multiarch.

This allowed me to easily and quickly debug all the executables having the correct envinroment variables and input.

Of all the crashes found I searched for the most easily controllable and one crash seemed promising, crash 3-5.

This crash directly controls the value of the return address, but how did I discover this? First, the concretized input is the following:

REMOTE_ADDR=192.168.1.1\00HTTP_HOST=objquery::Get obj val Failed!No object name to be added!:21588\00REQUEST_METHOD=HEAD\00SCRIPT_NAME=/cgi-bin/webproc\00CONTENT_LENGTH=14488\00CONTENT_TYPE=application/vnd.is-xpr\00QUERY_STRING=script%3Dvar%3Amod_ACL\00HTTP_COOKIE=sessionid='%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', '%s'='%s', @&~*ppp:١٢٣;language=Send %04x-POST msg failed!;sys_UserName=var:sys_Token␡set𝑻𝒉𝒆 𝒒𝒖𝒊𝒄𝒌 𝒃𝒓𝒐𝒘𝒏 𝒇𝒐𝒙 𝒋𝒖𝒎𝒑𝒔 𝒐𝒗𝒆𝒓 𝒕𝒉𝒆 𝒍𝒂𝒛𝒚 𝒅𝒐𝒈;

FUZZTERM

%3AInternetGatewayDevice.WANDevice.1.WANConnectionDevice.3.X_TWSZ-COM_VLANID%3DContent-type%3A%20text/htm

This concretized input is split in two parts: the environment variables before FUZZTERM and the value sent to stdin as body of the requests after it.

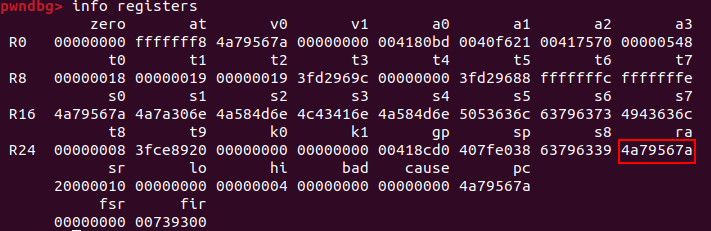

The registers at the time of the crash contain the following values:

As we can see the return address (which in MIPS is contained in a dedicated register called ra) is not part of any code section. and registers s0 through s7 seem to contain some ASCII pattern.

Usually at this point you would just search the bytes of your return address inside your input we have no match.

The registers which were overflowed contain a strange pattern when converted from hex to their ASCII representation, can you recognize it?

JyVzJz0nJXMnLCAnJXMnPSclcycsICcl

This looks like base64, given the presence of only lowercase and uppercase letters and repetition of patterns probably depending from the input.

Decoding it gives us the following string:

‘%s’=’%s’, ‘%s’=’%s’, ‘%

Which is part of our original input!

Given the low number of crashes and limited time, I did not set up a minimezer like Halfempty which meant I minimized the crash manually until I created the following input:

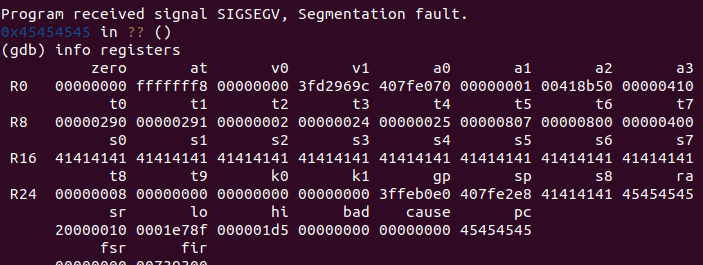

REMOTE_ADDR=192.168.1.1\00HTTP_HOST=192.168.1.1:21588\00REQUEST_METHOD=HEAD\00SCRIPT_NAME=/cgi-bin/webproc\00CONTENT_LENGTH=14488\00CONTENT_TYPE=application/vnd.is-xpr\00QUERY_STRING=\00HTTP_COOKIE=sessionid=AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAEEEE;

FUZZTERM

Which resulted in a controlled crash where all the registers from s0 to s7 contain AAAA (or, in hex 41414141) and the return address contains EEEE (or, in hex 45454545).

IF the cookie contains only regular ASCII characters no base64 encoding is applied, giving complete control over all stored registers and the return address register. We will see in the next blog post how this can be exploited to gain remote command execution.

Root cause analysis

It’s important to know the reason why a crash happens. This is useful for developers to fix the bug and for us to know the preconditions to corrupt the memory correctly.

The tooling made reconstructing the backtrace of the crash hard, and given the little time remaining I chose a… creative approach.

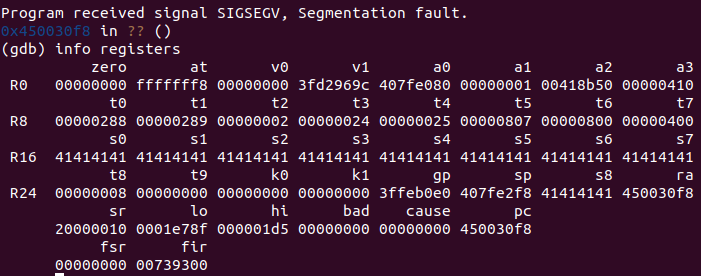

I decided to crash the program with different-length inputs and leak part of the address through the ra register by partially overwriting it.

This version of MIPS is big-endian, which means we will overwrite the most-significant bytes of the address. This meant I could leak the two least-significant bytes (as per screenshot above they are 30f8), since the others are my controlled value followed by a null-terminator.

By analysing the sections of the executable we could find the function which called the function triggering the overflow. This can be done by cycling over the sections and checking if:

- The section is executable

- The address pointed in the section makes sense

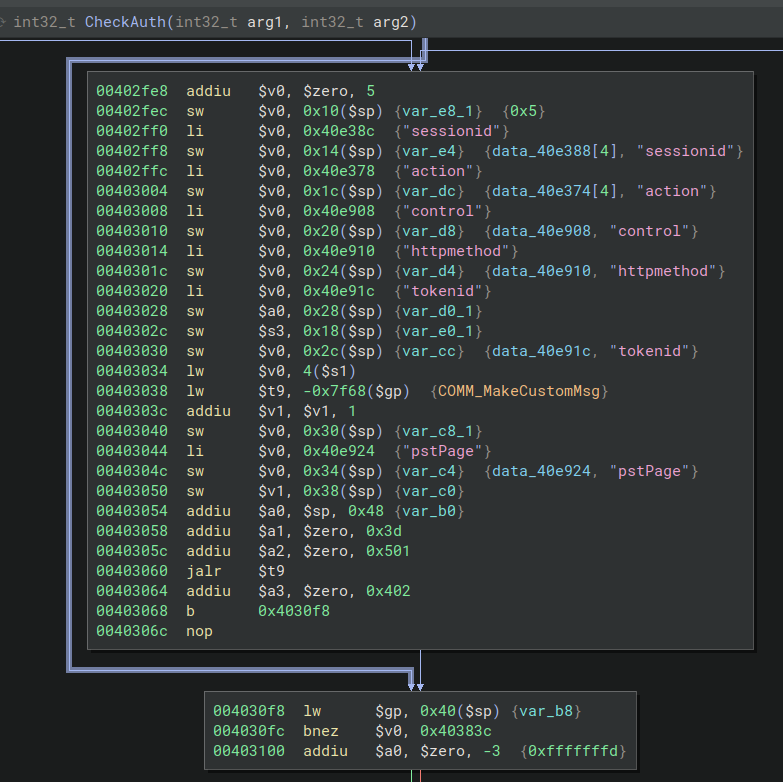

In this case the return address simply pointed at the data section fo the CGI binary, and we know it’s the right one because it’s right after a jump as seen in the Binary Ninja graph shown in the screenshot (at the bottom see address 0x004030f8).

But what are we looking at?

This function is used by the webproc binary to verify if the user is logged in. To do this it checks if a cookie named sessionid exists and then it validates and assigns a privilege level. (This is not pictured, as it’s not interesting for this vulnerability)

This is supported by the the minized testcase shown previously, where the sessionid cookie contains the data present in the overflow.

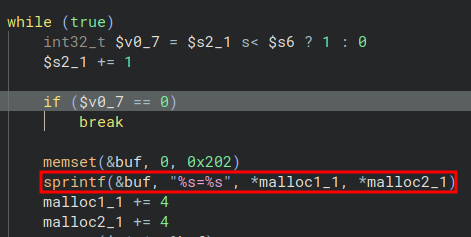

The actual bug is in the COMM_MakeCustomMsg function, from the libssap library.

In this function a buffer is created on the stack (not pictured) and then the buffer contents are set to 0 using memset. The sprintf function is then used to fill the buffer with a formatted string, using two strings from the heap.

sprintf is a dangerous function, because it does not check the bounds of the formatted data before saving it. In this case the length of buf is smaller than the length of the data written in it, leading to an overflow on the buffer onto the rest of the stack.

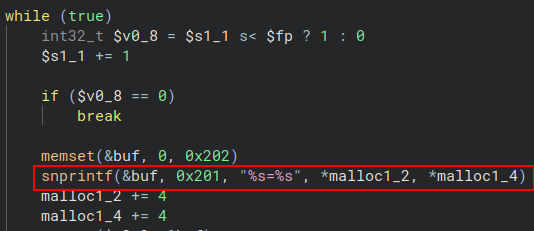

D-Link responded with an advisory10 and the following fix:

The only difference is the usage of the snprintf function which, differently from sprintf, does check the bounds before saving it in the buffer.

In this case the bound is set to 512 bytes which fits into the 513 byte buffer (the additional byte is for a null-byte as a string terminator) resolving the buffer overflow.

In the next post

In the next post we will exploit the vulnerability found through fuzzing, talk about MIPS exploitation and the reasoning behind writing a ROP gadget plugin for Binary Ninja.

If you have questions or suggestions, you can email me at max[at]sparrrgh[dot]me.

Footnotes

-

Andrea Fioraldi, Daniele Cono D’Elia, and Davide Balzarotti. The use of likely invariants as feedback for fuzzers. In 30th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 21). ↩

-

Andrea Fioraldi, Daniele Cono D’Elia, and Leonardo Querzoni. “Fuzzing binaries for memory safety errors with QASan”. In 2020 IEEE Secure Development Conference (SecDev), 2020. ↩